Why Did Putin Invade Ukraine?

However much he'd like you to believe it, the cause wasn't NATO or EU expansion. So, what was it? Why did he really go to war?

The day before I wrote this post, President Putin addressed both houses of the Russian Parliament. Once again, he blamed the West for “unleashing this war”. He blamed NATO and EU expansion, claimed the West wanted to “strategically defeat” Russia and stated that Russian territories and culture were under threat.

This is all smoke and mirrors. It is a fabrication that bears only the thinest resemblance to reality and ignores the facts. It is an attempt to mislead the Russian people into supporting the "‘Special Military Operation’ in Ukraine, and to undermine Western resolve to stop him. He wants the anti-establishment community in the West to buy his narrative and oppose robust responses from their governments.

His lies and fabrications are working. Many Russians do believe him, and I’m frequently hearing the opinion expressed on UK social media and amongst some British and American commentators that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was indeed provoked by the European Union and NATO, primarily by their expansion and the incorporation of former republics of the Soviet Union.

They echo President Putin’s assertion that it was the West that started this war. Many repeat Putin’s claim that NATO gave Russia a pledge not to expand towards the East and they point to this as a demonstration of bad faith on the part of NATO, suggesting that it’s reasonable for the Russians not to trust the alliance and to question it’s agenda.

I do agree that Vladimir Putin has been unable to accept and reconcile himself to the breakup of the Soviet Union – indeed, he’s said this himself – and I also believe that he’s seen the expansion of the EU and NATO to include former Soviet states as rubbing salt into the wound and that the breakup of the USSR are wrongs that must he thinks must be righted.

However, Putin and his apologists seem to have forgotten, or are ignoring the fact, that these are independent sovereign states that he’s talking about, countries that gained their independence legally and without bloodshed. And I do not accept that the EU or NATO are blameworthy. Things are not so black and white.

So, let’s examine all this.

Let’s start with whether NATO did or did not promise that it wouldn’t expand to the East and, if so, did it break that promise and, if it did, was that reason enough to invade Ukraine?

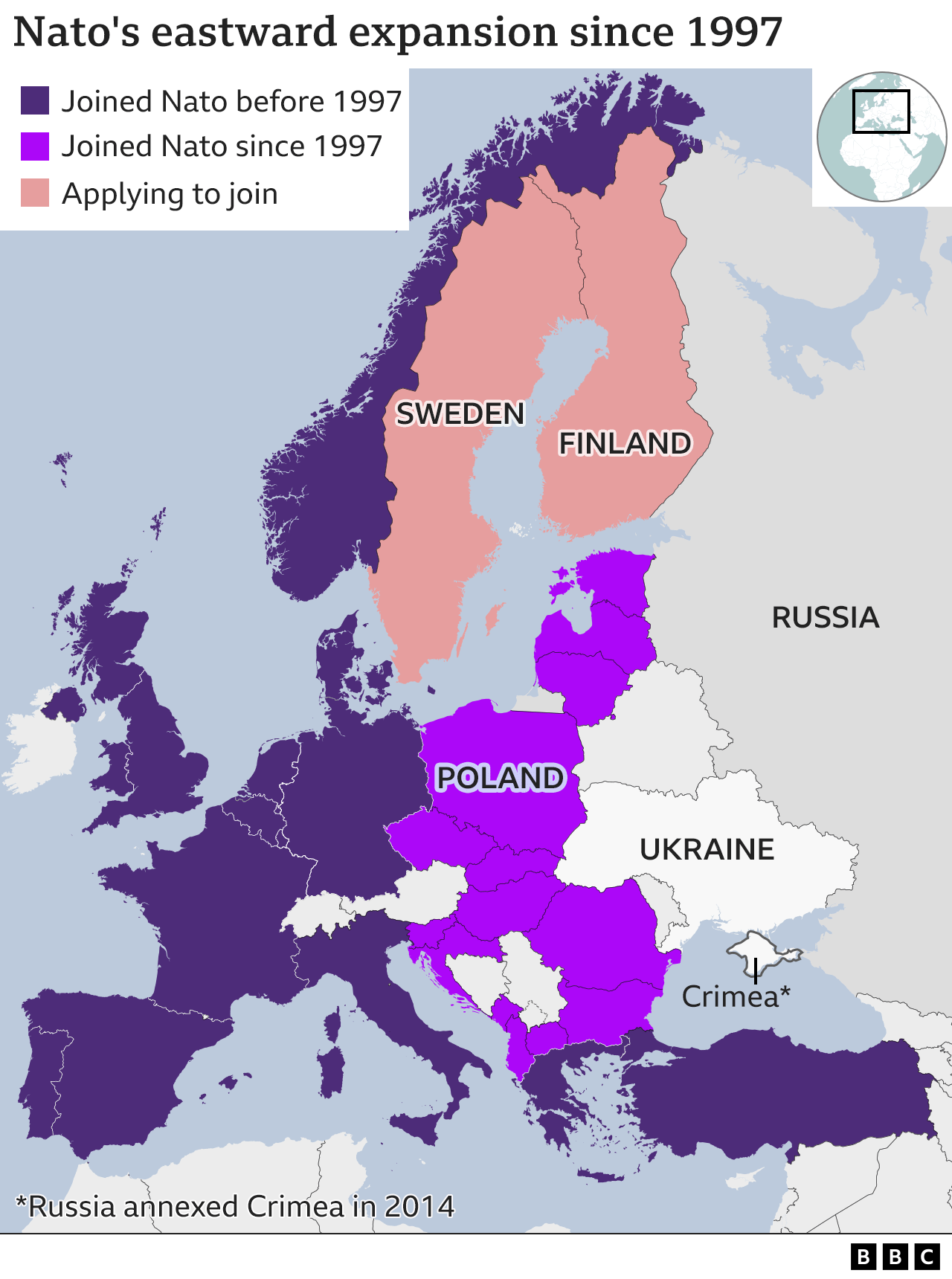

The first thing to point out is that NATO deployed no troops at all in the eastern part of the alliance until 2017, when it deployed four multinational battlegroups on a rotational basis to the three Baltic states and Poland. Even then, NATO only did so in response to Russia's annexation of Crimea and occupation of the Donbas and four battlegroups is tiny, compared with the 115 such groups that Russia deployed to Ukraine.

Secondly, the reality is that the only comments and agreements made to the then Soviet Union regarding NATO expansion were in the context of the reunification of Germany, over 30 years ago.

During those talks, US Secretary of State, James Baker did tell Soviet President Michael Gorbachev, that "if we maintain a presence in a Germany that is a part of NATO, there would be no extension of NATO's jurisdiction for forces 1 inch to the east.” Or, as he put it to Germany’s Chancellor, Helmut Khol, “…NATO’s jurisdiction would not shift 1 inch eastward from its present position."

It’s important to emphasise that these talks related only NATO “extension” into what was then East Germany. The subject did not cover or relate to expanding NATO membership to other countries.

Perhaps the most authoritative source we have regarding those discussion is Mikhail Gorbachev himself, who said:

"The topic of ‘NATO expansion’ was not discussed at all, and it wasn’t brought up in those years. I say this with full responsibility. Not a single Eastern European country raised the issue, not even after the Warsaw Pact ceased to exist in 1991.

None the less, in 1990, Russian President, Boris Yeltsin, did protest against NATO’s expansion on the grounds that NATO had specifically agreed not to expand. In response, the US administration, then under President Clinton, asked the German foreign ministry to investigate whether any German official had given any assurances that NATO would not expand. The Germans responded that Yeltsin’s complaint was wrong, but it said it could understand "why Yeltsin thought that NATO had committed itself not to extend beyond its 1990 limits”.

Then, in 1991 the Germans told British and US legislators that "We had made it clear during the [German reunification] negotiations that we would not extend NATO beyond the Elbe (a river in Germany), confirming Secretary of State Baker’s words to Gorbachev.

So, if we agree that Baker did state that NATO would not “extend 1 inch to the East” the question is whether the Soviets had reasonable grounds for thinking that a concrete assurance that NATO would never expand its membership to include former Soviet republics. No. Why not?

The first point is that no discussion, debate or talk about NATO extension East mentioned any other country in Europe other than Germany. As Gorbachev himself states, it was “not discussed at all, and it wasn’t brought up in those years... Not a single Eastern European country raised the issue.” Why didn’t they? Why did Russia not raise it?

The reason is simple. At that time the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact (the Soviet led military alliance equivalent to NATO) were fully intact. The now independent NATO members: Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and Romania, were then members of the still existing Warsaw Pact. And Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia were still an integral part of the Soviet Union. In that context any idea or consideration of the possibility that NATO might expanpand to incorporate those countries would have been completely bizarre.

Secondly, the Soviets knew perfectly well, as do the Russians do now, that unilateral comments from US and/or German officials cannot be taken as an agreement or assurance from NATO.

NATO, as Putin knows very well, takes all such decisions in the format of the North Atlantic Council, at which all NATO member States are represented.

There’s no doubt that the Kremlin knew this. Russia and NATO worked closely together in the Russia-NATO Council and Russia maintained a delegation to NATO until 2021 when they closed it due to allegations that the delegation had been engaged in spying. They know very well how decision making in NATO works.

So, did the North Atlantic Council take any did any NATO, take any such decision or did any NATO official give suggest to the Soviets that NATO would not expand its membership? No.

Russian officials are many things, but they are not thick… Senior Kremlin officials know perfectly well that no US or German official could give any sort of assurance on behalf of NATO’s North Atlantic Council without the Council formally taking a decision to that effect.

No, the idea that the West gave any even vaguely concrete or credible assurances to the then Soviet Union that NATO would not expand to incorporate any newly independent, former Soviet republics, or former Warsaw Pact members is for the birds.

What is for certain is that the idea that such assurances were given has been cited by President Putin as one of his mendacious excuses for invading Ukraine.

In my opinion, those repeating it are naively supporting the Kremlin propaganda machine.

But…

…that said, let us, for a moment, consider whether, if even if such an assurance had been given, and broken, would it really justify Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Of course, if a country wanted to avoid war in such circumstances, you would expect its government to engage in a fervent diplomatic effort to resolve the issue by non-military means. So, we must ask, were there any fora available in which the Kremlin could have raised it’s concerns and tried to get them addressed, before resorting to war.

The answer is Yes.

The little heard of, but very important Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (or OSCE) is based in Vienna. The OSCE has 57 participating States. It is the northern Hemisphere’s primary conflict prevention body established in 1975 by something called the Helsinki Final Act.

The Helsinki Final Act was an effort to reduce tension between the Soviet and Western blocs. The accords were negotiated and signed by all the countries of Europe and by the United States and Canada. The agreement recognised the inviolability of the post-World War II frontiers in Europe and pledged the 35 signatory nations to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms, and to cooperate in economic, scientific, humanitarian, and other areas. The idea for the Helsinki Final Act came from the Soviet Union and was accepted by NATO.

Furthermore, the Helsinki Final Act, to which the Soviet Union was, and Russia is a signatory, has formed the basic principles of European Security ever since. Importantly, it enshrines the fundamental principle that every sovereign nation has the right to choose its own security arrangements. In other words, Russia, as a signatory, formally recognises that it has no right to interfere with the security arrangements of any other nation.

Whether that nation joins NATO or not, is a sovereign decision, wise or otherwise.

Then, in 1994, in the OSCE Ministerial Council in Budapest, Russia, the US and the UK confirmed their recognition of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine becoming parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. The so called ‘Budapest Memoranda’ committed those three countries to abandoning their nuclear arsenal to Russia.

In return for the signatories - Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine – giving up their nuclear weapons to Russia, Russia, the US and the UK also agreed to:

1. Respect the signatory's independence and sovereignty in the existing borders.

2. Refrain from the threat or the use of force against the signatory.

3. Refrain from economic coercion designed to subordinate the sovereignty of any of the signatories and thus to secure advantages of any kind.

4. Seek immediate UN Security Council action to provide assistance to the signatory if they "should become a victim of an act of aggression or an object of a threat of aggression in which nuclear weapons are used".

5. Refrain from the use of nuclear arms against the signatory.

6. Consult with one another if questions arise regarding those commitments

It’s interesting to point out here that, in compliance with its Budapest Memoranda commitments, Ukraine handed its nuclear arsenal to Moscow, in return for Russia committing to respect Ukraine’s independence and sovereignty within its existing borders, that is its borders as of 1994.

So, if we’re arguing about whether NATO made any commitment not to expand its membership to Eastern European countries – which, as we have established, it did not – what about Russia’s commitment to respect Ukraine’s independence and sovereignty, within its 1994 borders, in return for Ukraine handing over its nuclear arsenal to Moscow, which it did, in 1997.

In addition to the Helsinki Founding Act and the Budapest Memoranda, Russia also signed the NATO-Russia Founding Act in 1997. In doing so, Russia pledged, again, to uphold:

"Respect for sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of all states and their inherent right to choose the means to ensure their own security".

Both the Helsinki Final Act and the NATO-Russia Founding Act name the OSCE as the forum as the forum for addressing disputes regarding implementation of and adherence to those agreements, and as the organisation tasked with implementing confidence building measures to reassure its 57 participating States and mitigate conflict risks from lack of transparency.

A year before, in 1996, the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly (56, now 57 countries, including Russia) issued the OSCE Stockholm Declaration. The Declaration recognises concerns over the enlargement of security organisations, established the principle that expansion cannot be considered in isolation and strengthened the role of the OSCE in establishing mutual confidence and transparency to preventing misunderstanding and conflict resulting from expansion.

The Declaration, signed by Russia, after the independence of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, and after the break-up of the Warsaw Pact, also, - and I must stress this - reaffirmed the fundamental OSCE principles that each participating State maintains the inherent right to choose or change its security arrangements, including treaties of alliance, as they evolve, and that no participating State will strengthen its security at the expense of the security of other States or regard any part of the OSCE region as its sphere of influence.

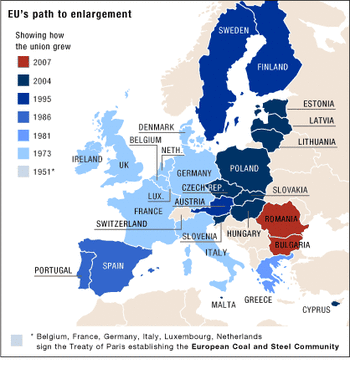

Russia signed up to this. In doing so, Russia agreed that Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic), Romania, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia had “the inherent right to choose or change their security arrangements, including treaties of alliance, as they evolve”.

And, let me point out that the OSCE Permanent Council is the primary forum for addressing concerns regarding European security architecture and threats. All ambassadorial Permanent Representatives of the 57 participating States, including the Russian Federation, meet in the Council every week, in Vienna.

Furthermore, the good offices of the OSCE Chairman in Office and Secretary General are available to all participating States, to assist with mediation.

So, returning to the question, did Putin have a forum to turn to, in which any concerns over EU and NATO expansion could be properly and effectively raised and addressed? The answer is a very, very clear and unambiguous YES! He did – The OSCE.

The OSCE Permanent Councill is not an annual thing, it’s not a monthly thing. It is a weekly thing. Putin has had countless opportunities to seek a resolution in that forum over the years – but did he?

Yes. He did.

But…

…only two months before Russian invaded Ukraine.

He did not raise it when Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Latvia, Lithuania or Estonia joined either NATO or the EU.

The answer is, yes, he did raise it in the OSCE Permanent Council.

But…

…not before invading Georgia in 2008.

He also didn’t raise it before annexing Crimea and parts of the Donbas.

…or before he deployed his invasion force to Ukraine’s borders.

He only raised it two months before he launched the war last year, and then he did not raise his concerns for discussion and resolution. He presented a list of demands that fundamentally, if they’d been agreed to, would have consigned the principles and commitments of the Helsinki Final Act, Budapest memoranda, Stockholm Declaration and Russia-NATO Founding Act to history, and with them the commitments and principles of European Security that had kept the peace for over 75 years. Putin knew full well that such demands could not be agreed to.

So, presenting demands in the OSCE, that NATO withdraw to its pre-1990 positions, can only be seen as posturing for his domestic Russian and his anti-establishment Western audiences.

He’d clearly decided to go to war at that stage, but wanted to evade blame for starting it by being able to say “look, I raised my concerns and I got nowhere. I’ve had no choice now but to launch a Special Military Operation.” He knows that the Russian people would not support a war initiated by the Kremlin, and so, had to blame the West, and this is how he did it.

He continues to this day. His address to both Houses of the Russian Parliament on February 21st this year was largely on that theme. He stated – and I quote – “It was the West who unleashed this war”. He needs the Russian people to believe that, or he’ll lose their support. And, if some in the West happen to swallow it too, and oppose Western governments in their efforts to uphold the principles of European security, so much the better for him.

The presentation of the Kremlin’s demands was theatre. It was, to use Russian word that doesn’t translate precisely into English, maskirovka – a tactic to mask the truth, to muddy the facts, to create ambiguity, to deceive and manipulate one’s opponent.

And remember, NATO did not deploy any troops to former Soviet States until 2017 and then only in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Moreover, any military analyst, including those in the Russian armed forces, could tell you that the NATO forces stationed in in the Baltic states and Poland are far too small in number and capability to launch any form of offensive operations into Russian territory.

The idea that they could, or that they pose any credible threat to Russia, is for the birds. Their presence has always been defensive and is largely symbolic, to demonstrate the alliance’s collective commitment to defence in response to Russia’s aggression.

So…

No agreement regarding NATO expansion had been given.

Russia invaded Georgia in 2008 and seized the Crimea without going to the OSCE to attempt to resolve any concerns beforehand.

Russia didn’t take any concerns to the OSCE until two months before the invasion of Ukraine, and then only to make demands it knew could not possibly be agreed to.

Russia invaded Ukraine in violation of the commitment it gave Ukraine to respect its independence and sovereignty within its 1994 borders, in return for Ukraine handing over its nuclear weapons to Russia.

By invading Ukraine, Putin violated the commitments and principles it’d signed up to in the Helsinki Final Act, Budapest memoranda, Stockholm Declaration and Russia-NATO Founding Act.

The conclusion is inescapable:

Putin invaded Ukraine because he wanted to.

What about the EU

When it comes to the European Union, there is a more valid case to make that it’s naïve, rather than deliberate actions, did contribute, significantly to Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine.

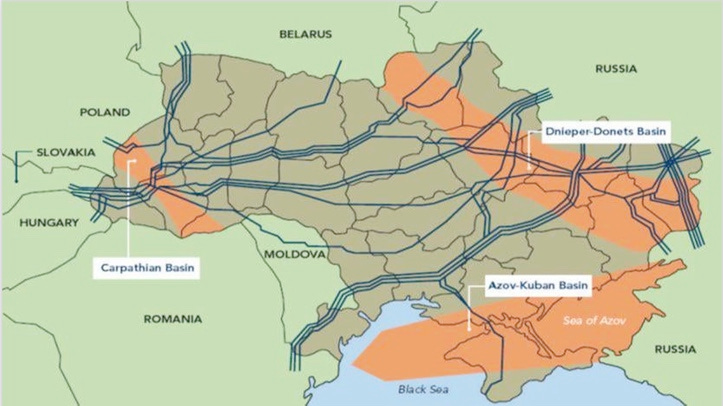

But what we must recognise, before talking about the European Union’s ‘contribution’ to Putin deciding to go to war, that Kyiv’s relationship with the EU only became a contributory factor because it unwittingly converged with something else, the discovery of gas in the Black Sea and the Donbas. EU enlargement became a threat to Putin because of that. Let me explain.

In 2012 significant deposits of natural gas were discovered under the Black Sea in Ukrainian waters.

Ukraine had neither the expertise nor the equipment to exploit the Crimean Black Sea reserves. Therefore, Kyiv was always going to have to award licences to foreign companies.

Given the close historical, cultural and political relationships between Ukraine and Russia, President Putin had assumed that the Yanukovych government in Kyiv would favour awarding the licences to a Russian company, giving Russia access to that gas and a say in who it was sold to and under what conditions.

But, In August 2012, Ukraine announced an accord with an Exxon-led group to extract oil and gas from its Black Sea waters. The Exxon team had outbid Lukoil, a Russian company.

Then, in 2012-2014, Ukraine negotiated the development of Skifske field with an Exxon Mobil-led consortium that also included Shell and the Romanian company OMV Petrom. Again, the Yanukovych government rejected Russia’s Lukoil bid.

In yet another development, this time related to Eastern Crimean oil fields, Ukraine signed an agreement Italy’s Eni S.p.A. and France’s EDF energy companies.

Huge deposits of shale gas, believed to be the third largest in Europe at 1.2 trillion cubic metres, have also been discovered under the Donbas. Like the deposits under the Black Sea, Russia hoped to get the licence to exploit the Yuzivska field in Donetsk, but Kyiv awarded the contract to the Shell oil company in 2013.

Putin was furious. But to understand why Russia’s bids for the licences were repeatedly rejected, we have to go back to 2005 when Viktor Yushchenko was elected Ukrainian President. At that time Ukraine was not only importing all its gas from Russia, it was also the main transit route for Russian gas exports to the European Union member States.

Yushchenko’s politics favoured closer relations with the EU. In 2004, during his Presidential campaign, he was poisoned with dioxin. It was then, and still is assumed that the failed assassination was an attempt by the Kremlin to stop him becoming President and to end his policy of closer links with Western Europe. Why?

Because of the deep historical and cultural relationship between Ukraine and Russia, Putin saw then, with some justification, as he still does, that if Ukraine becomes prosperous and stable with EU cash, and is able to offer its citizens a good standard of living, it will pose a risk to social and political stability in Russia as the Russian public demands better for themselves.

When, in 2005, having survived the assassination attempt, Yushchenko became President, the Kremlin had to take another tack.

Russian gas giant Gazprom increased the price of gas for Ukraine by over 200% from $50 per 1,000 cubic metres, to $160 per 1,000 cubic metres. Large scale corruption in Ukraine and the unlawful extraction of huge amounts of Russian transiting Ukraine en-route to the EU had a large part to play in the following dispute, but to resolve these issue would take time, so Yushchenko agreed to pay the higher prices but only over time, stating that Ukrainian industry would become unprofitable with gas above $90.

Putin himself then threatened to cut Ukraine’s supply and in December 2006 Gazprom stated that the new price would have to be 220–230 per 1,000 cubic meters 4.5 times higher. In the end, the dispute was resolved, after a fashion, but arguments over gas prices and transit rights continued.

Ukraine’s dependence on Russian gas and this cat and mouse game over gas prices and supplies posed a serious risk to the Ukrainian economy and domestic retail fuel prices. It is for that reason that the government of Victor Yanukovich, who became President in 2010, was so reluctant to issue licences to Russian companies to exploit its Black Sea and Donbas gas reserves. He also embarked upon a policy Ukraine gradually moving towards exploitation of its own reserves, reducing its dependence on Russia for gas, and gaining energy independence.

Now, here is where the EU’s enlargement agenda and naivety come in.

Separately from all this wrangling between Kyiv and Moscow over gas supply and licences, the EU and Kyiv had concurrently been holding talks on an EU-Ukraine Association Agreement.

The Kremlin was fully aware of these talks. Indeed, Putin himself had attended some of the discussions and expressed no concerns. However, things became edgy in 2012, when Putin realised that Ukraine had so much gas and was not going to be letting Russian companies exploit it.

Two issues converged: 1) The existence of huge gas reserves under the Crimean Black Sea and Donbas 2) the imminent signing of an EU-Ukraine Trade Association Agreement.

In other words, Putin was faced not only with the prospect Ukrainian energy independence from Russia, but also because of the policies of the Ukrainian government, with the independence of EU member States from Russian gas.

Such a scenario would massively reduce Russian gas revenues, have a significant impact on the Russian economy and hugely reduce Russian political and diplomatic leverage over the European Union and its member States.

From a Russian national interest perspective, such a situation would be economically, socially and diplomatically disastrous, and had to be avoided.

However, war was still not a certainty at that point. Putin had not, at that time, decided on the use of force. I believe that he still hoped to achieve his ends by non-military means.

Instead of war, the Kremlin’s response was to put pressure on Viktor Yanukovych’s Ukrainian government to back out of the EU Association Agreement.

Putin threatened to close Russian borders to Ukrainian goods and cut Ukraine off from Russian gas. Such a move would have decimated the Ukrainian economy. Yanukovic had little choice. In November 2013, he backed out of the Association Agreement and instead adopted a policy of pursuing closer trade and financial ties with Russia.

What both Putin and Yanukovic had failed to appreciate, was the strength of feeling amongst the Ukrainian people, who were appalled at what they saw as the strong arming of Ukraine by the Kremlin. They had their hearts set on closer integration with the European Union and when Yanukovich pulled out of the Association Agreement they took to the streets in the protests that became known as the ‘EuroMaidan’.

In early December, Baroness Ashton, High Representative of the European Union External Action Service – effectively the EU’s Foreign Minister – visited Kyiv and, rather than conducting a neutral and objective visit, she was went to Kyiv’s Independence Square to meet protesters. In doing so, she took sides in what had, until that moment, been a domestic political matter. Putin was infuriated.

In January 2014, the protests became violent with numerous protesters being shot by Ukrainian special police.

On February 21st, President Yanukovic fled Ukraine for Russia.

On February 24th, Baroness Ashton again visited Kyiv.

It was obvious to Putin that he had lost all political, diplomatic and financial leverage over Kyiv and that Ukraine was on a firm trajectory towards closer EU integration, with the implication that, indeed, the scenario he’d hoped to prevent i.e. Ukrainian, and by association EU gas independence from Russia, was now pretty much a certainty.

His only course of action to prevent this, was to deny both Ukraine and the EU and access to the gas fields.

And on February 27th Russian troops – little green men – moved into the Crimea. Russia seized the Peninsula, and with it, the Ukrainian Black Sea gas deposits, estimated to be in the region of 4 to 13 trillion cubic metres.

Russia also seized the subsidiaries of Ukraine’s state energy conglomerate in Crimea, Naftogaz and appropriated billions of dollars of hi-tech equipment.

In one move, Putin had ended Kyiv’s offshore oil and gas operations.

Concurrently, with the occupation of Crimea, Russian armed and equipped separatists, supported by what the Kremlin later described as “military specialists”, seized Ukrainian government buildings and declared independence in Donetsk and Luhansk districts. Following initial gains by the separatists in seizing control of the entire Donbas region, Ukraine launched a counter-offensive that succeeded in pushing the Russia forces off some of the key terrain they needed to deny access to the gas deposits.

Putin’s annexation of Crimea and his attempt to seize the Donbas with its shale gas deposits was nothing to do with NATO expansion or EU enlargement, but everything to do with undermining Ukrainian and European Union energy and gas diversification strategies and independence from Russia.

He only partially succeeded.

Whilst Crimea was his, the Donbas was not. Instead, the Donbas became, in effect, a stand-off that left the major shale gas fields in Ukrainian hands. Ukraine had lost 45% of its coal reserves to Russia, but not the gas. Furthermore, there were still significant gas deposits in Kharkiv district, and he now had the serious logistical problem of supporting Crimea without any land link between the peninsula and Russia proper.

The logistical situation was unsustainable, and Putin had not yet achieved his strategic aim. Russia still risked losing its leverage over the European Union because he’d not yet succeeded in fully ending Ukrainian and European prospects of gas independence.

To resolve the situation, Putin had some work to do. He had to

Take the entire territory of Donetsk and Luhansk districts, to deny their gas deposits Ukraine - This could only be done by force of arms.

Ideally seize control of the gas deposits in Kharkiv district – This too could only be achieve by force of arms

Solve the Crimean logistical challenge.

The Crimean problem could be mitigated in the medium term by a bridge from Russia to the peninsula and indeed construction of such a bridge was completed in 2018. But in the longer term, it was clear that only a secure land link, along the northern coast of the Sea of Azov, to Russia, would suffice. That in turn, could also only be achieved by force of arms.

That is why, when Russian forces started to mass on Ukraine’s borders in 2021, I was sure that war would follow.

I’ve explained why the Russo-Ukraine war is all about denying Ukraine and the EU energy independence from Russian gas and thus preventing the loss of Russian diplomatic leverage over them. But Europe already had an intention to move away from fossil fuels and towards renewables and, it could be argued that Russia was, going to lose influence in any case, so why go to war?

To answer that, we have to recognise that Europe’s green energy and diversification strategies were not a thing when Putin embarked upon his strategy in 2014.

Secondly, those green diversification strategies are in any case long-term strategies and, from the perspective of 2014, dependence on Russian gas was still going to be relevant for some time. Ironically, Putin’s aggression in Ukraine has accelerated European efforts to accelerate diversification. That brings me to the third point…

The the Russian economy is almost entirely dependent upon revenues from its gas exports. Grasping that one of Europe’s first responses to his actions in Ukraine would be to accelerate energy independence, Putin himself has accelerated Moscow’s energetic engagement on building alterative markets across Asia; markets that are not subjected to any green energy agendas and will be only too happy to purchase cheap Russian gas for the foreseeable future. So, taking control of Ukrainian deposits to supply those markets, and keep the revenues flowing from them, makes Putin’s war a win-win.

There’s a slightly circular argument here as well, which demonstrates the veracity of my assertion…

…Supplying Asian gas markets means utilising Russian domestic supplies and backfilling them with Crimean gas to maintain Russia’s own demands. That necessitates secure gas pipelines along the northern coast of the Azov Sea that can connect with Russia’s internal gas distribution network. And that significantly reinforces the need for Putin to establish a secure land corridor.

Conclusion

So, there we have it… Putin’s strategic aim was to deny Ukrainian and European Union independence from Russian gas. When he lost political influence over the decisions made in Kyiv, he had to turn to military means to achieve his aim. From that point, seizing control of the Crimean gas fields, the Donbass shale gas fields, the Crimean land bridge and, ideally, Kharkiv’s gas fields, became his war objectives and, in keeping with his own bitter irredentist beliefs, he’s utilised Russian patriotism, by fabricating a series of threats from the West, to solicit Russian popular support for his actions.